I am very pleased to say that Otago University Press are going to publish Can’t Get There from Here: New Zealand’s Shrinking Passenger Rail Network, 1920–2020, my collaboration with mapmaker Sam van der Weerden. The book will come out in 2021; it is tentatively scheduled for September.

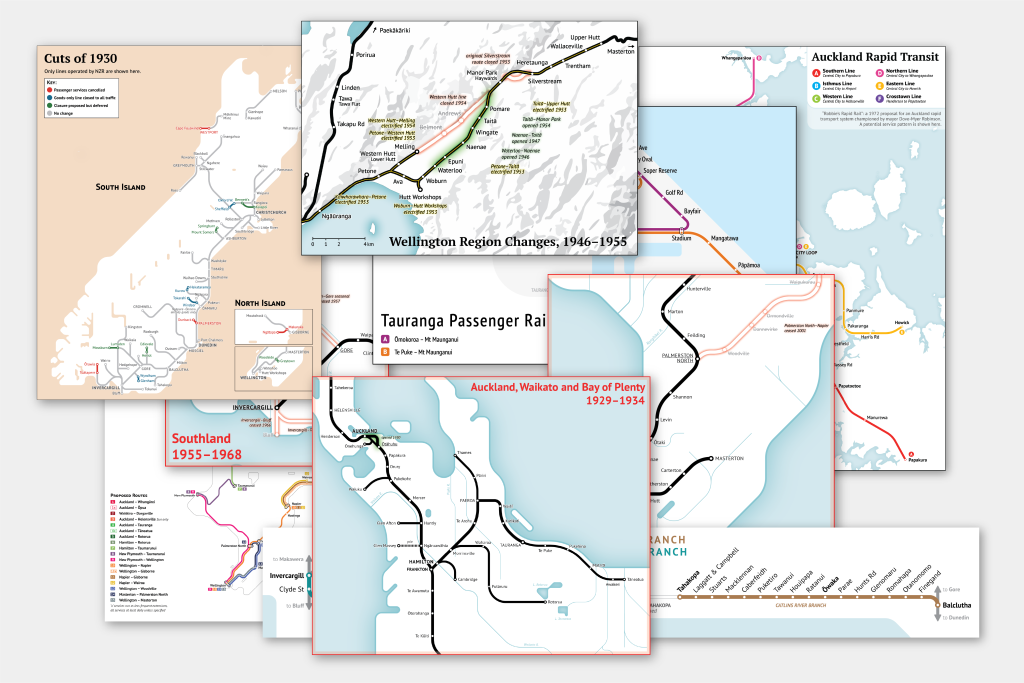

It will be lavishly illustrated. Sam’s maps look incredible, as you can see from the sample below. There will also be at least sixty photos, some never before published (even on social media! quite a feat if you know me). I’ve included a handful of low-res samples in this entry.

The text is, I believe, one of the most thoroughly researched narratives on New Zealand railway history to date. It draws heavily on Archives New Zealand’s vast collection of New Zealand Railways (NZR) files, as well as material held at repositories such as the Hocken Library and Southland District Council Archives. It also makes use of newspapers—not just those on Papers Past; I’ve done my time with the microfilm machines—annual reports to parliament, consultants’ reports, autobiographies, and more.

The inspiration for Can’t Get There from Here came from an unlikely source: a late-night Twitter discussion about former passenger rail services in New Zealand. I made a little timeline of when each service started or finished for the past century, and the next morning it seemed like it would be worth my while to turn it into an article for a journal of historical geography. A few thousand words later and I realised I had a book on my hands. I also realised that I needed to work with a mapmaker or else the book would be inscrutable to anyone without a thorough knowledge of New Zealand geography. The very talented musician Anthonie Tonnon was another participant in that discussion, who introduced me to Sam and his mapmaking talents.

Credit: J.F. Le Cren, Archives New Zealand (ANZ) AAVK 6390 B31.

So, what’s the book all about? If you’ve tried to travel around New Zealand in the last couple of decades, you’ve probably realised that you won’t get far without a car. Rail patronage is booming in Auckland at the moment and Wellington has a longstanding electrified commuter network, but beyond those two cities you’re unlikely to find a passenger train, let alone one going your way. If you do, it’s probably a tourist service—KiwiRail brands these as the Great Journeys of New Zealand, slow and expensive trains for leisure travel. Good luck finding the Everyday Rapid Journeys of New Zealand, efficient and affordable trains for people such as business travellers, families, or local shoppers.

It was not always like this! I’m a millennial from the Kāpiti Coast who grew up poring over railway books, and I suspect most of my peers and those younger than me haven’t a clue that passenger trains used to criss-cross both islands. After all, why would they know this? If you were fifteen in 2002, as I was, long-distance rail travel in New Zealand was basically dead. But New Zealand once had good passenger rail, and it could have it again. Nothing was inevitable about its decline, and the outcomes of economic and social change were not predetermined or inexorable. The choices of people shaped the network, politicians and stationmasters alike.

In 1920, you could travel to pretty much any reasonably sized town by train, and many tiny villages too. If you saw a railway line, a passenger train would almost certainly come along sooner or later. Things changed a little by 1967, but at the start of the year trains could still take you to most major destinations and a handful of rather obscure ones. Things changed a lot by 1982, but even at the start of that year you could catch a suburban train in Dunedin or trundle along the rails through northern Taranaki. Now, if you come upon a railway outside Auckland or Wellington, it probably only carries freight.

Why did the network contract? I thought a good way to understand this would be to look at how it has evolved over the past century. I decided to investigate not just when but also why each service started or finished.

Can’t Get There from Here shows that the contraction of New Zealand’s passenger rail network was partly the result of technological change and mainly the outcome of deliberate decisions and government policies. The rise of private motor transport brought an end to the expansion of rural passenger services in the 1920s. As early as 1924, many officials within NZR believed that improved services competitive with road were unaffordable—often over-estimating the cost of upgrades. The effects of the Great Depression compounded this decline and NZR hoped to save money by cancelling services to lightly populated areas. It also began using buses rather than trains to carry some passengers. This became increasingly common from the mid-1930s: bureaucrats perceived buses as more modern and efficient, even as travellers questioned their motives—were buses better, or just a way to charge passengers more for the same journey?

Credit: A.P. Godber, Alexander Turnbull Library (ATL) APG-0324-1/2-G.

World War II spurred completion of major interprovincial railways as petrol and tyre shortages stimulated record train patronage. Trains were essential to domestic mobility at wartime, but the arrival of peace brought serious problems—the railways were rundown and coal shortages reduced train frequency and reliability. Passengers shifted modes. Bureaucrats continued to prefer buses; the allure of American-style freeways attracted politicians. NZR cut services in the belief this met demand where it was, sometimes at the insistence of Treasury; in reality, this further dissuaded potential travellers. It might go without saying that I am a little more critical of senior NZR management and their decision-making than some previous authors have been—a few were former NZR men themselves.

By the 1970s, passenger rail had gone from an everyday form of transport to one that was increasingly unfashionable and unprofitable. Politicians from both Labour and National dithered and then rejected opportunities to revitalise services; some railway administrators even cancelled some routes in underhanded ways to avoid public criticism. Ridership statistics were routinely taken as the full extent of the market for train travel, with no attempts made to grow patronage. There were meaningful attempts to improve and expand rail between 1987 and 1991, but this was a false dawn. Service cancellations in October 2001 and February 2002 left New Zealand with a passenger rail network smaller than at any time since 1877.

Credit: Manawatū Heritage / Palmerston North City Library 2007N_Rm30_RAI_0678

The final chapter looks to the future. I could not conclude the book without indicating developments that are already on the cards—Te Huia between Hamilton and Auckland will start running in early 2021, and Auckland’s City Rail Link is planned to open in 2024. I also felt that the preceding chapters suggested further possibilities. Sam and I have prepared maps and text that propose options for our cities and regions. These are historically-informed conversation starters that show how we can improve mobility for all New Zealanders. Fundamentally, we believe that rail transport is important for our communities, essential to improving mobility, and a valuable technology to address the effects of climate change.

And, yes, if you are an REM fan, you’ve probably guessed the source of the title:

Hands down, Calechee bound Landlocked, kiss the ground Dirt of seven continents going 'round and 'round Go on ahead, Mr Citywide, hypnotised, suit-and-tied Gentlemen, testify (I've been there, I know the way) Can't get there from here (I've been there, I know the way) Can't get there from here

Last, here are a few images that I think are going to miss the cut. They are still low-res, just in case they do sneak in, but please enjoy.

Credit: J.F. Le Cren, ANZ AAVK 6390 B1446.

Credit: Whites Aviation, ATL WA-37584-F

As a person grown up on rail travel in the UK.

It’s a shame that newzealand doesn’t have a passenger,

Rail service any more.I wish there was a train from hawes bay

To Rotorua I would use it all the time.

As the road from Napier is terrible.

Bring back rail travel

LikeLike

My copy of the book arrived today. I look forward to unwrapping it for Xmas.

LikeLike

As of December 2021, New Zealand appears to have lost all possibility of enabling people to get around the country by train. KiwiRail has suspended Auckland-Wellington and Picton-Christchurch “till the middle of 2022”, and there are no guarantees that what may resume after that time will be usable by ordinary travellers not wanting a “tourist experience”. It is incomprehensible that this has become the case in a first-world country, in the 2020’s. Where do we go from here? We can hardly sink any lower! But the darkest hours are those just before dawn. It is time for a complete re-birth of passenger train travel in New Zealand and this will require fresh people with fresh ideas to make it happen. I refuse to be pessimistic about this. All the indications are that this needs to happen. I believe it will happen. I just can’t see how, at the moment.

LikeLike

I have only glanced at the book, and therefore apologise if I missed the drift of the book which to me seemed to overemphasise regional and local services that are very much a thing of the past. I mean the Greytown and Waiaku (Gleenbrook ) branches could still have relevant passenger services, but the Southland branches were probably only of interest for Vulcan railcar services because maybe a second aluminium smelter and other industrial developments could have occured along the Riverton, Colac Bay Branch.

The three rail lines into Central Otago were the sort of thing that made NZ notorious with Capitalist interests in the US, Dominion office and Treasury in the UK in 1920s and 1930s. Although of course if they had completed the line up the lake from Kingston to Queenstown ( Frankton) the Southerner might have been viable as a Christchurch Queenstown luxury and or backpacker service

LikeLike

Robert, thank you for commenting but I suggest you do more than glance at a book before commenting on its content, let alone offering a critique. As pages 15–16 of the introduction set out clearly, the book “is an account of the passenger network’s evolution. It describes the first or last regularly scheduled passenger service on every railway line to show why a region or town obtained a service and what decisions guided its demise” because “Little-noticed decisions in the regions often presage big changes in cities, and this is abundantly true for rail. This book gives prominence to trains that might not feature elsewhere or may be passed over as trivial.”

LikeLike

I’m looking forward to buying your book in Canada when it’s published here on April 29th. I’m interested in passenger rail worldwide and would like to read about how the rail system has declined in New Zealand. I think there may be some parallels with the situation here in Canada. Thanks for the informative website.

LikeLike