Earlier this year, I found myself explaining to friends and students alike that Australians do not mark separate labelled boxes to vote at referendums on altering the federal constitution. Voters instead write the word Yes or No in a single box. It’s been so long since a constitutional referendum that this is no longer common knowledge—nobody under 42 has voted in one, and those under 53 have only voted on two simultaneous referendums in 1999.

My interlocutors grasped quickly that this method reduces informal voting, especially when referendums occur alongside general elections. Public debate, however, took a sinister turn in the couple of months leading up to the referendum. From anonymous social media accounts right up to Opposition leader Peter Dutton, there has been consternation—even conspiratorial claims—about the rules for counting ballots.

Legislation contains something called savings provisions, which enable votes to be counted where a voter’s intention is clear despite not following instructions precisely. At referendums, ballots marked only with a cross (an “X”) are informal. They do not count. Ticks, however, can usually be counted as Yes.

This is the source of the displeasure. United Australia Party senator Ralph Babet and party funder/founder Clive Palmer even took the matter to the High Court (and failed). But, as psephologist Kevin Bonham explains, today’s outraged politicians had many occasions to propose amendments. They were inattentive to savings provisions until complaints became useful politically.

Yet it never should have been an issue, because informal ballots have not affected any referendum outcome. Fewer than 1% of ballots in the 1999 referendums were informal—for any reason, including blank ballots and crude symbols. ABC election analyst Antony Green highlights that at a 2009 Western Australian state referendum only 199 ballots, 0.02% of the total issued, were rejected for being marked with a cross

The topic does, however, raise important historical questions, especially as some objections treat the savings provisions as something new: a surprise or a trick by the Albanese government and/or the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC). How long have we voted this way? Have we voted differently in the past? Has a cross ever been valid?

Let me take you through nearly 120 years of federal referendums. We must put aside state and territorial referendums, as the federal story is complex by itself; the states and territories have sometimes used their own methods.

Voting in 2023

First, before delving into over a century of change, let’s be clear about the upcoming referendum. It contains one—and only one—question, on a proposed amendment to the federal constitution to create an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, which will give non-binding advice to parliament.

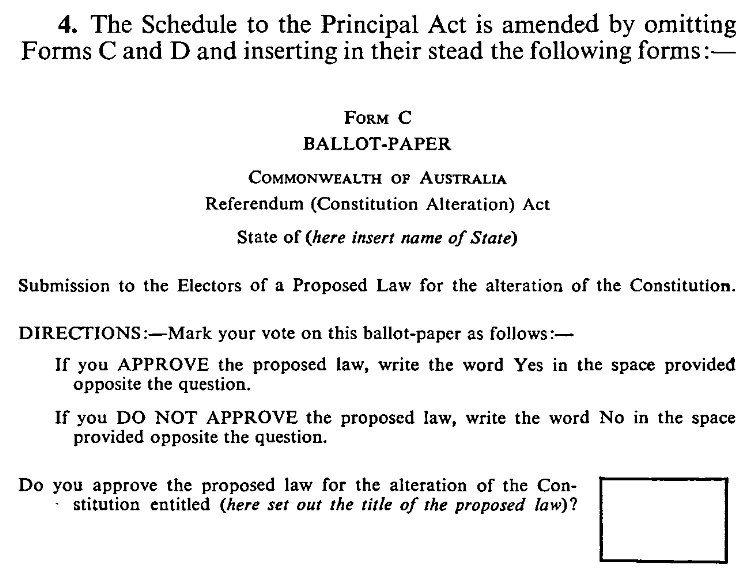

A referendum must be a Yes/No question. Voters are left in no doubt to write the words Yes or No to indicate support or opposition.

Moreover, if a voter makes an error, section 93(8) of the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 (Cth) enables ballots to be counted “according to the voter’s intention, so far as that intention is clear”. A tick, a common signifier of assent, is an unmistakable Yes so long as no other mark on the ballot introduces ambiguity.

A cross, however, has multiple uses. It can imply dissent. But thousands of international travellers land at our airports daily clutching arrival cards with crosses marking affirmative declarations. Every reader will have used a cross to show agreement on forms or surveys at some point in their life. Without any other mark on the ballot, scrutineers cannot infer if a cross signifies Yes or No, so the ballot is informal.

Earlier this year, the Albanese government passed the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Amendment Act 2023 (Cth). This added section 93(9) to make the savings provisions more precise: Y explicitly counts as Yes and N as No. We now have the most detailed, generous savings provisions for decades. Politicians upset about ticks and crosses had every opportunity to raise the issue during the amendment process; none did.

Have we ever voted with ticks or crosses, though? The way we are voting this year might feel novel, but it has a long history.

The first referendums, 1906–26

The Australian constitution can only be amended via referendum. Indeed, such is the significance that Australia has developed a unique terminological distinction: a “referendum” modifies the constitution while a “plebiscite” is on non-constitutional matters where parliament desires direct voter input. This distinction is not made internationally, nor here at state level.

The Deakin government in 1906 made the first attempt to change the constitution, and it had to create referendum machinery. The Referendum (Constitution Alteration) Act 1906 (Cth) set out a ballot paper for ongoing use. It instructed voters to make a cross in a box beside either Yes or No, according to their preference. A cross, therefore, indicated assent, not dissent.

The Referendum (Constitution Alteration) Act 1919 (Cth) added savings provisions that a ballot “shall be given effect to according to the voter’s intention, so far as his intention is clear”. Despite the gendered phrasing, this applied to all voters—with anonymous voting, it could not be otherwise.

So, Australians at first voted with crosses in referendums, but this did not last long. Two simultaneous referendums in 1926 were the last to instruct voters to mark crosses. In total, Australian voters were instructed to use crosses to show assent at 15 referendums plus two polls on military conscription in 1916 and 1917, which at the time were called referendums but are now categorised as plebiscites.

Preferential voting at referendums, 1928–51

Parliament introduced preferential voting at federal elections and by-elections from December 1918. A decade later, the Referendum (Constitution Alteration) Act 1928 (Cth) brought referendums into line. Voters who approved a change were instructed to write 1 in a box beside Yes and 2 in a box beside No; the reverse applied to reject the proposal.

This preferential system came with savings provisions. If a voter only marked 1, this was counted as if there was a 2 against the other option. If a voter only marked X, this was inferred to be a 1 and counted the same way as 1-only ballots—as with the previous system, X signified assent. Other ballots were counted if the “intention is clear”.

Preferential voting might seem unintuitive for binary Yes/No questions. Nonetheless, Australia used it at nine referendums between 1928 and 1951, plus for two compulsory postal ballots of woolgrowers in 1951 and 1965 that were called referendums by legislation and regulations.

The voting method since 1967

Australia held no constitutional referendum between 1951 and 1967, which was the longest gap until the current 24-year one. The Referendum (Constitution Alteration) Act (No 2) 1965 (Cth) introduced a new method of voting ahead of two simultaneous referendums, one on Aboriginal peoples and one on the “nexus” binding the size of the House to be double that of the Senate. Anticipated to occur during 1966, they were held simultaneously in early 1967.

The new system asked voters to write Yes or No in a single box. It inspired a memorable slogan for the 1967 Aboriginals referendum: “right wrongs, write Yes”. The current method of voting has, therefore, been on the books for almost 60 years—the longest of any federal referendum voting method. It has been used at 20 referendums so far, almost half the total.

The 1967 legislation repealed the savings provisions pertaining to preferences and crosses. Absent any other indication of a voter’s intent, ballots with crosses have been informal ever since. The act did, however, keep the general provision from 1919 to count ballots where “intention is clear”.

Refining the machinery

The Hawke government repealed and replaced all legislation relating to referendums with the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 (Cth). This legislation did not change the method of voting, and section 93(8) retained the savings provision to count ballots where “intention is clear”.

Parliament established the AEC as an independent statutory authority in the same year. Ahead of four simultaneous referendums in 1988, the AEC received legal advice from the Australian Government Solicitor respecting ticks and crosses. This advice, which has been renewed since, confirmed that ticks unambiguously indicate approval but that crosses are more complicated.

The meaning of a cross is contextual, as noted earlier. If there are multiple questions on the ballot and a voter uses a mixture of ticks and crosses, a scrutineer can potentially infer that crosses signify disapproval.

When there is only one question—as there will be this year—the meaning of a cross is unclear. Is the voter marking the box to approve the proposal, as they might on other forms? Or are they invoking a negative connotation? Scrutineers are not mind-readers and the AEC must operate within the bounds of legislation and legal advice.

Recent exceptions

Australians have been instructed to write the words Yes or No at every federal constitutional referendum since 1967. There have, however, been two other federal questions that used different methods.

In 1977, Australians voted on four referendums and one plebiscite. The plebiscite was about the national song; it asked electors to rank “Advance Australia Fair”, “God Save the Queen”, “Song of Australia”, and “Waltzing Matilda”. “Advance Australia Fair” won easily, receiving 43.29% of first preferences nationally and a plurality in every state and territory except the ACT (“Waltzing Matilda”) and SA (“Song of Australia”).

Four decades later, the Turnbull government directed the Australian Bureau of Statistics to conduct a survey of eligible voters on marriage equality. It did so to resolve disagreements both within its ranks and between the houses of parliament.

The 2017 marriage equality form was a voluntary postal survey, although its resemblance to a referendum or plebiscite has understandably led many people to describe it as such. It is also the only time since 1965 that a cross has been accepted as a formal vote: the ballot instructed those surveyed to “mark one box only”, Yes or No.

Conclusion: crosses, preferences, or words?

Perhaps the 2017 postal survey is why some people believe that the instruction to write Yes or No, and the rejection of ballots marked with a cross, are new innovations. The history of referendums shows they are not.

Likely, too, the unprecedented gap between referendums has accentuated the novelty of this voting method. The 2000s and 2010s are the only decades during which Australians have not voted in a constitutional referendum since they first voted to approve the constitution in 1898–1900.

But there is no reason to assume a cross means No. When Australians have been instructed to use a cross, be it in early twentieth century referendums or the 2017 postal survey, they used it to mark their preferred option—not to express disapproval, as this year’s malcontents believe it should be counted.

Australians marked a cross in a box for Yes or No at the first fifteen referendums, held between 1906 and 1926. Two passed. The next nine referendums, between 1928 and 1951, required preferences; again, two passed. At the most recent twenty referendums, between 1967 and 1999, voters have written the words Yes or No in a single box; four passed.

We will find out tomorrow the fate of the 45th referendum. The voting instructions are clear, informality rates are low, and referendums are rarely close. The few times a referendum outcome has been tight, No prevailed because of the high barrier to success: Yes requires a majority of the nationwide formal vote and a majority of formal votes in a majority of states.

Ticks being formal and crosses being informal will not skew the outcome. Opportunities to revise this aspect of conducting referendums have not been taken: bellowing now about the formality of ticks versus crosses achieves nothing, fosters baseless conspiracies, and might increase informal voting.

The method of voting at referendums is the product of almost 120 years of experience, and the current method is the most enduring. Whichever way you choose to vote this year, your ballot will be formal so long as you write either Yes or No.

(Acknowledgements: this article derives from a Twitter thread and numerous replies contributed beneficially to the process of revision. Thank you to all who engaged. I intended to place this article in a more prominent outlet but my everyday duties of lecturing and marking got ahead of me, so with the referendum imminent, I decided to post it here on my website in the hope it reaches some interested readers.)