I have written about Tangiwai before, for an academic journal and a blog, and to publish Ted Brett’s account in the Stuff newspapers on the 60th anniversary. This piece for the 70th anniversary is an experiment in narrative history. I have focused specifically on individuals for whom I have personal accounts, seeking to integrate them together. There are, naturally, so many other stories of bravery and tragedy that go unmentioned here, but this is hopefully a glimpse into how those involved in Tangiwai experienced that night. I take especial interest in this disaster as Ted Brett was my grandfather. At the end is a list of primary sources and a brief discussion of them. All quotes of direct speech are as they were remembered by the people who spoke or heard them; they are not my creations.

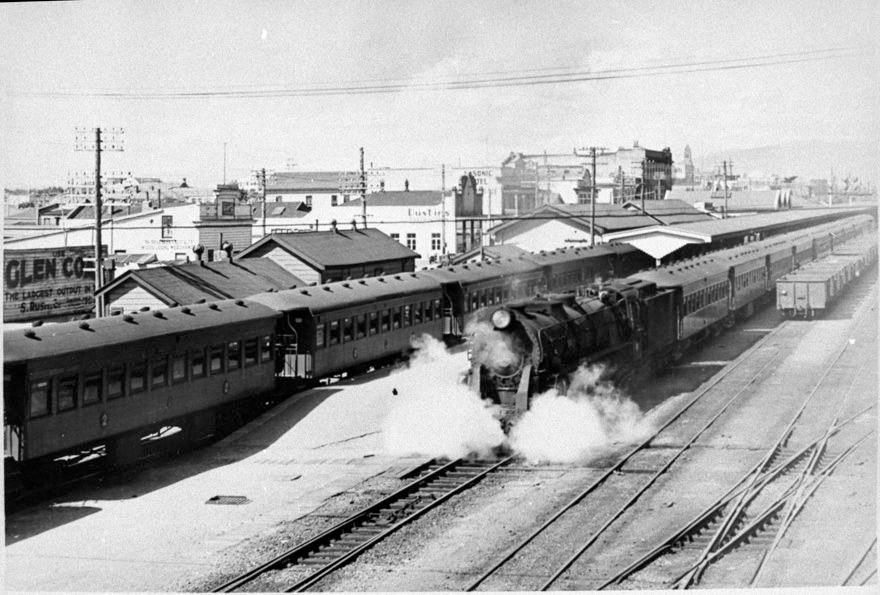

Christmas Eve, Thursday 24 December 1953. Wellington railway station was bustling in the mid-afternoon. Announcements directed passengers to electric multiple units for Johnsonville, Paekākāriki, and Taitā, steam-hauled local trains for Upper Hutt and other lower North Island destinations, and to platform nine for the 3pm express to Auckland.

Oil-burning steam locomotive KA 949 sat at the front of the eleven-carriage express, train number 626 on the working timetable supplied to staff of New Zealand Railways (NZR). Behind the engine were five second-class carriages, four first-class carriages, a guard’s van, and finally a Railways Travelling Post Office van. It was one of multiple trains laid on that day for holidaymakers travelling the North Island Main Trunk between New Zealand’s capital and its largest city.

1953 had the makings of a very special Christmas: Queen Elizabeth II had arrived in Auckland on 23 December and many travellers hoped to see this first visit of a reigning monarch to New Zealand. The popular young queen captivated a country in the midst of economic golden weather and postwar optimism for the future. As the clock ticked towards 3pm, the last passengers said their goodbyes and hastened aboard, excited for what lay ahead.

A couple of hours later, 18-year-old Ted Brett waited for the express to arrive in Palmerston North—not at today’s station on the edge of town, but at the original station located centrally on Main Street a couple of blocks over from The Square. His birth certificate gave his name as Richard Edward Brett, but to everyone he was simply Ted, son of John and Edith of 100 South Road, Masterton. He had arrived in Palmerston North earlier that day aboard a railcar with his best friend, 17-year-old John Cockburn, John’s 12-year-old brother Douglas, and other travellers from the Wairarapa.

Not long after 5:30pm, Ted caught sight of “the mighty beast” KA 949 leading the train. In the cab were Charlie Parker, an experienced driver, and Lance Redman, a similarly respected fireman. In the guard’s van, William Inglis did not have to look after tickets, small lots of goods, and the train’s general safety all by himself: he had an assistant, Hemi Ransfield, while car attendant William Allaway aided passengers. In the postal van, meanwhile, Malcolm Kay and Ronald “Junior” Price busily sorted and distributed last-minute Christmas mail.

After some confusion about Ted, John, and Douglas’s seats, guard Inglis directed them to the second carriage behind the locomotive. The express had a ten-minute stop at Palmerston North and then resumed working its way up the island, passing through Feilding, Marton, and Taihape. At Waiōuru, eight people disembarked and one boarded, bringing the total aboard to 285: 176 second-class passengers, 102 first-class passengers, five railway crew, and two postal agents.

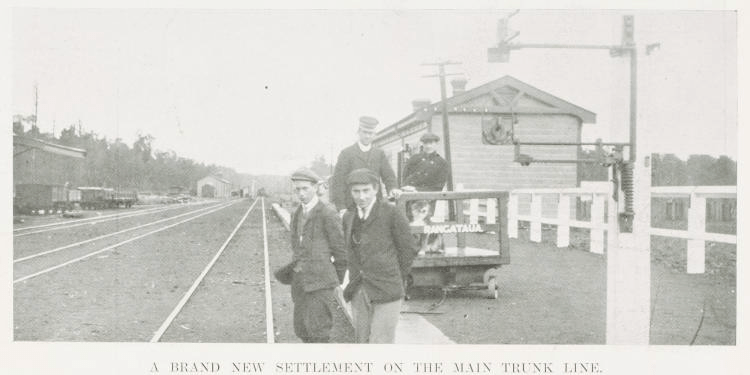

The train steamed out of Waiōuru on time at 10:09pm and Parker and Redman began building up speed. From here to Ohakune, the train could travel at up to 50mph (80km/h) across the Central Plateau south of Mount Ruapehu, fast by the standards of the time. After winding through a series of curves, the Main Trunk entered a straight near the village of Tangiwai, where it crosses a road we know today as State Highway 49. Both road and railway then cross the Whangaehu River about 1.5km west of Tangiwai railway station, the railway just north of the road.

The express passed Tangiwai at 10:20pm. Most passengers had settled in for the night. John and Douglas were dozing in the second carriage, like the mothers and young children seated near them. Ted, though, was still awake. An enthusiastic photographer, he hoped to make a movie of Mount Ruapehu at night, and, luckily for him, the night was clear and the weather fine.

At Tangiwai, the locomotive crew exchanged a tablet to permit travel on the next stretch of line. A mechanical tablet exchanger enabled this safeworking procedure to be performed without slowing the train. Parker and Redman received the tablet authorising their onward passage while the station agent observed the express. The headlight was on full, as were other safety lights, and the train was travelling slightly below maximum line speed, closer to 40mph (65km/h) than the permitted 50mph. All seemed well: the train was on time, the night was clear, and the weather fine.

Around five minutes earlier, however, two men in a car found something perplexing and ominous. Robert Somerville and Trevor Wildbore were driving from Ohakune in the opposite direction to the train, and when they approached the Whangaehu River, they were surprised to find the road covered by a noisy torrent of water. Ahead of them, a car with a caravan had pulled up too late and it was now stuck. Two occupants called for help with a third who had become faint, with the water rushing above their knees. The Whangaehu was usually shallow and this flood made no sense, because the night was clear and the weather fine.

On the other side of the river, driving a truck in the same direction as the train, 27-year-old Taihape postal clerk Cyril Ellis made a similar discovery while on a journey to visit his parents for Christmas. At about 10:15pm, he, his wife, and his mother-in-law found their passage blocked by “turbulent, yellow water” across the road bridge. Ellis parked at a safe distance, then got out to investigate. The Whangaehu was roaring over the road bridge: all he could see in the beam of his powerful torch was the top wooden side rail as the river rose and fell. When Ellis turned towards Waiōuru, he spotted a powerful light a mile back at the Tangiwai level crossing—the headlight of KA 949. After all, the night was clear and the weather fine.

Ellis’s torch could not illuminate the railway bridge, but he feared the worst. The railway line was about fifty metres from where he had stopped, so, leaping a barbed wire fence, he sprinted to the track and ran towards the locomotive, waving his torch. As the train barrelled past him, Ellis yelled to the crew but could not tell if Parker or Redman saw him. Maybe they saw Ellis or maybe the headlight of KA 949 illuminated the river: they braked a couple of hundred metres from the bridge.

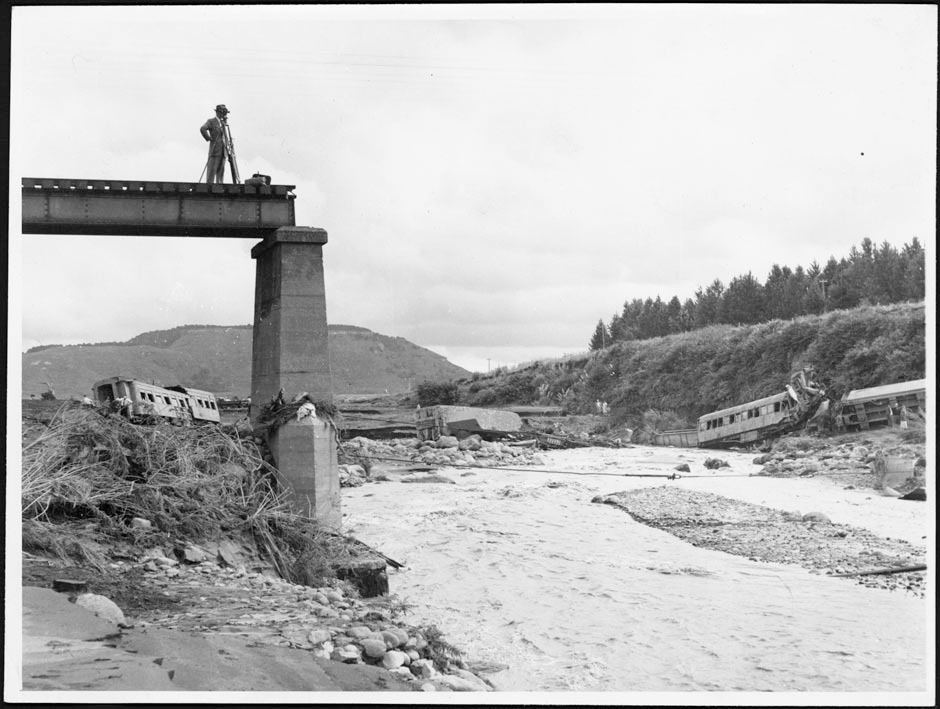

The night was clear and the weather fine, but what nobody aboard train number 626 nor on the road west of Tangiwai knew was that a tephra dam containing the crater lake of Mount Ruapehu had collapsed a few hours earlier. This unleashed a torrent of mud, water, and volcanic ash known as a lahar. There had been lahars in the Whangaehu before, but only one since the Main Trunk was opened, which in 1925 scoured pier 4 but did not destroy the bridge. It was repaired, and numerous inspections in the following 28 years deemed the bridge structurally sound. This time, however, the lahar was too strong and pier 4 could not resist it. Nor could the road bridge, which collapsed at the Waiōuru end.

On the Ohakune side of the river, another car heading towards Waiōuru found its passage blocked and stopped alongside those already there. The driver hopped out and both he and Wildbore spotted the headlight of the express.

“I wonder whether the rail bridge has gone”, remarked Wildbore.

“We shall soon see”, replied the other man, possibly Arthur Dewar Bell.

Wildbore had a torch but he could not even get close to casting light on the bridge. Both men watched helplessly, as did Ellis on the other bank. Parker and Redman desperately tried to stop the train, and in the second carriage Ted Brett heard a “terrible screeching of metal on metal” as the emergency brakes took effect. The sparks were visible to Wildbore on the opposite bank.

It was not enough. “The engine simply nose-dived”, recalled Ellis a couple of days later. It entered the river with a “bellowing splash”. The carriages, in Wildbore’s words, “appeared to topple into the river”. Joan Karam, a passenger aboard the third carriage, felt the train rattle and lurch before being “dumped into space with unbelievable violence”.

Ted, in the second carriage, tried to wake John as the train swayed and rose upwards. Then, in his words, “everything just seemed to be folding back on itself. We seemed to be sliding, rising, twisting, turning—then we seemed to drop.” The carriage plunged into a whirlpool of ice-cold sulphuric water.

Immersion. Destruction. Pure unrelenting horror.

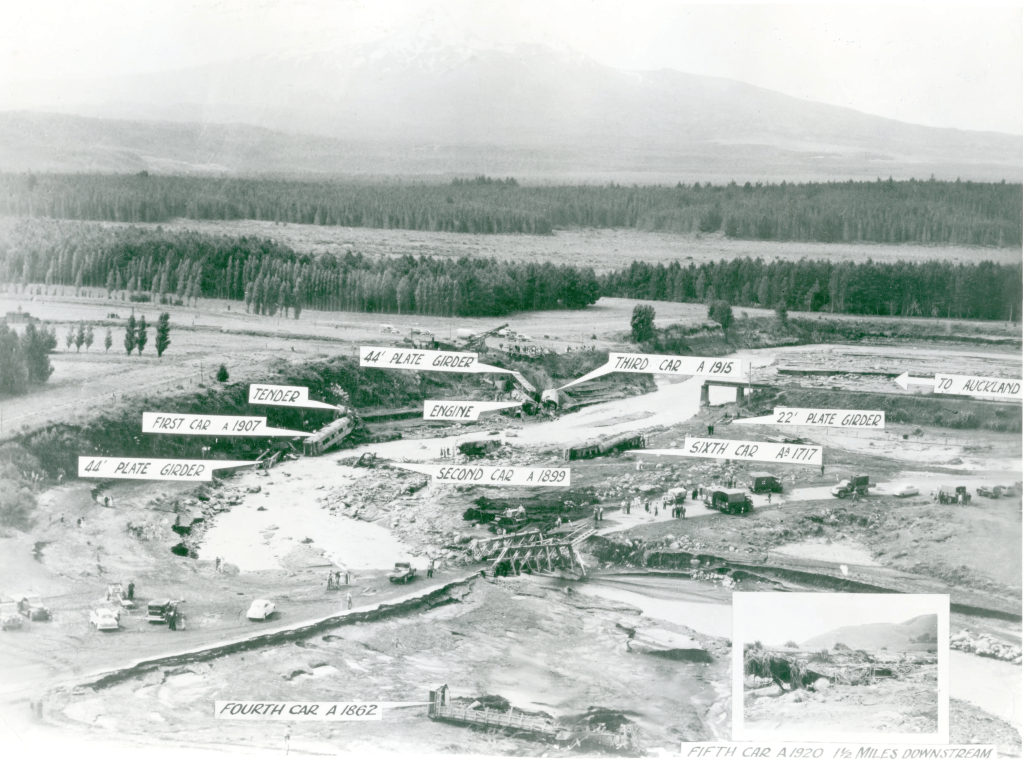

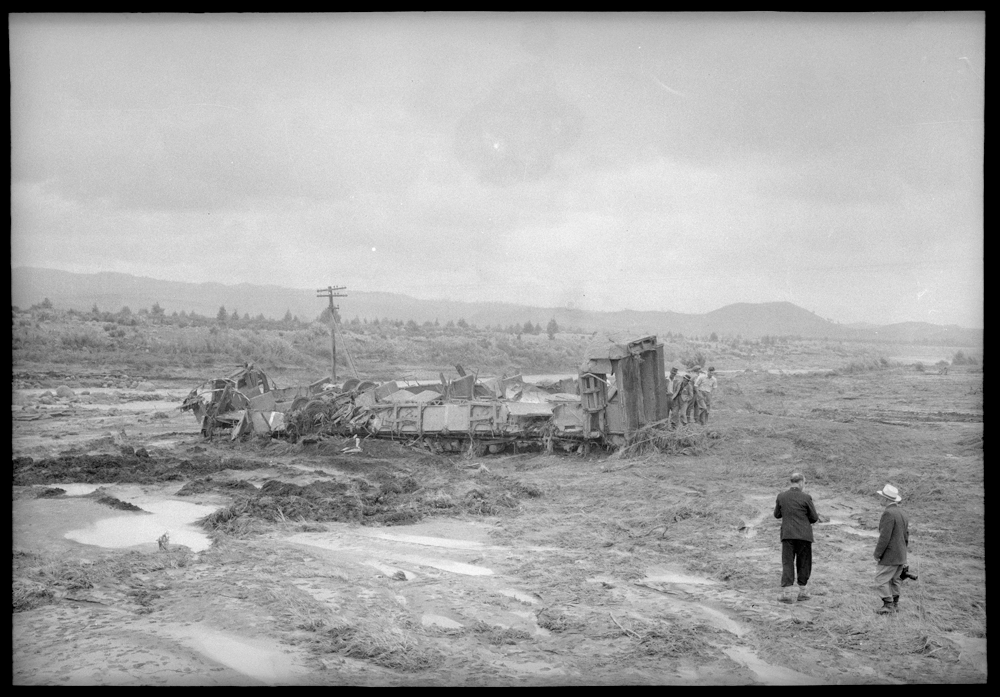

KA 949 nearly hit the opposite bank, as did the first carriage. The third carriage was torn in two. The torrent carried the fourth carriage across the road, dumping it past the road bridge, one set of wheels atop the twisted remains. The fifth carriage was swept further: its remnants came to rest 2.5km downstream. The sixth carriage, the leading first-class carriage, teetered precariously on the edge of the shattered bridge. As for the second carriage, it was shredded into an unrecognisable lump of metal. Ted smashed at a window and forced his way out as the carriage disintegrated around him.

The rear half of the train remained on the track. Cyril Ellis, frantic, ran towards the guard’s van. A confused William Inglis hopped out to investigate why his train had stopped unexpectedly, fortuitously doing so on the same side of the train as Ellis.

“I tried to stop him! I tried to stop him!” yelled Ellis frantically. “I tried to stop him, but he was going too fast. Half your train is in the river!”

“No!” replied a disbelieving Inglis.

“It is! It is!” insisted Ellis, as they hurried towards the front of the train.

Both men entered the sixth carriage, whose lights were still burning, and advised the passengers to remain calm. Inglis walked to the front of the carriage and looked out the door. All he could see were a few feet of broken rails in empty air above a swollen river. He and Ellis, independent of each other, later recounted the words that came from his mouth: “Good God, there is an engine and five cars in there!”

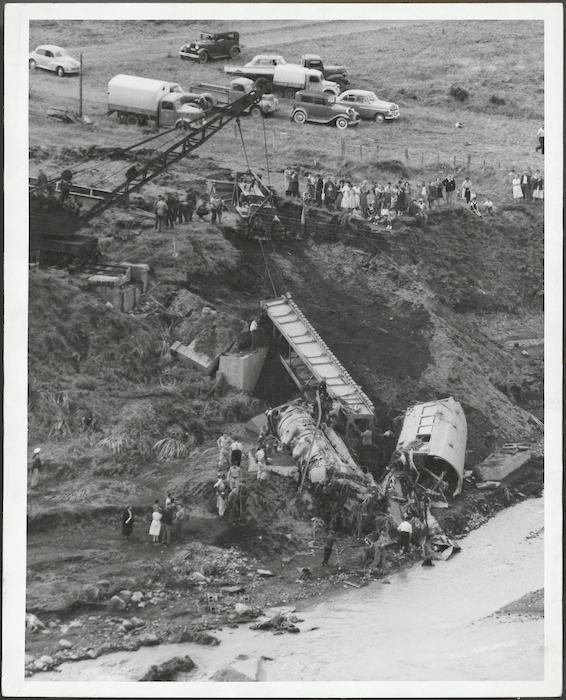

It was about to be six. The coupler holding the sixth carriage to the rest of the train suddenly snapped, everything tilted, the lights went out, and the carriage toppled off the bridge. Most passengers had been standing, ready to evacuate, and Inglis shouted for everyone to hold onto the luggage racks as the carriage bobbed in the river. He was standing on a seat, water up to his armpit, when the carriage rolled onto its side and came to rest on the riverbank.

There was only about a foot of air between the windows and the water level inside the sixth carriage, and floating large items of luggage made things all the more hazardous. Inglis wriggled out a smashed window. Ellis broke another with his elbow and feet, and helped a passenger, John Holman, rescue his wife.

Ellis and Holman then plunged back into the carriage and, in Inglis’s words, “did all that was humanly possible to assist”. A young woman, Suzanne Kennedy, was trapped under other people and broken seats and drowned before the carriage came to rest, but the other 21 passengers escaped, including Kennedy’s sister.

As the last people were lifted through the windows, Ellis stood on the side of the carriage, his energy spent: “I can’t do any more, I am exhausted.” By this point, more motorists had arrived on the scene and the waters had receded far enough that they could form a human chain to bring people to safety. Ellis reflected later that “I cannot explain what we went through, but somehow in the stress of the moment John and I seemed to have terrific strength.”

Those in the front half of the train were much less fortunate. Of the two locomotive crew and 176 second-class passengers who fell into the river, just 28 survived. KA 949 struck and shattered pier 3 of the bridge on its way to the riverbed. Charlie Parker’s family identified the body of the engine driver, but fireman Lance Redman was swept away, never to be found. The locomotive’s tender burst, adding oil to the cocktail of the lahar. Passengers in the river screamed for help, not knowing if anyone could hear them.

Ted Brett, blood coursing down his arms from forcing his way out of the second carriage, feared he accidentally kicked away other people in his desperation to escape. He did, however, probably save at least one life: he bumped against something small, and he clung to it, especially after it appeared to move. Late in life, Ted described it as a “pillow”, too humble to take any greater credit as he was blinded in the water.

By sheer good fortune, he found himself in a part of the river sheltered by the first carriage. He had recently gone rock-climbing with friends in Wellington and this possibly gave him the ability and wherewithal to scramble clear of the torrent, still holding the “pillow”. Only once he reached solid ground near one end of the first carriage did he realise his clothes were shredded, he was freezing, his right fist had swollen to an enormous size, and his entire body ached.

”I didn’t even know the damn river’s name. I didn’t know where I was. Almost didn’t know who I was.”

In the wreckage of one half of the third carriage, Joan Karam clung to a luggage rack to keep her head above the waterline. She struggled to process what had happened, initially believing the train had been swept out to sea until she realised the water was not salty—instead, the carriage had come to rest, and icy water was rushing through it. Joan yelled and yelled for her sister Madeline, but no response. She felt the hand of somebody underwater, who she pulled to the surface: another young woman whom Joan knew only as Anne.

The two women were buffeted by objects hard and soft in the water, including dead bodies. “It was sickening”, she remembered. They had to get out. Joan pulled herself through a smashed window and then helped Anne. They perched on the carriage and took stock of their surroundings: they were beside a girder of the bridge and the engine, still hissing and hot to the touch. On the other side of the river, they could see the rear half of the train, its lights faintly illuminating the rescue operation at the sixth carriage. And, in the distance on their own side, a hopeful sign: torches moving along the riverbank.

Robert Somerville first heard cries for help coming from downstream, on the other side of the road from the railway bridge. The water was subsiding, but darkness and smoke made it difficult to find the person calling out. Eventually, he found a man almost fifty metres from the road but separated by turbulent water. Although muddy, it turned out to be only thigh deep. Somerville then made his way towards the railway bridge, coming upon six men from the first carriage, uninjured but covered in silt. They informed him more people were alive down the bank.

Trevor Wildbore, meanwhile, had gone to raise the alarm with another motorist who had recently arrived on the scene, Alan Stuart of Taumarunui. They drove to the nearby Forest Service station in Karioi, and found the offices illuminated but unattended. The staff left lights on overnight to keep a load on their generator, but Wildbore and Stuart were not to know that their yelling and banging on the door was perfectly useless. One of them smashed a window to gain access and place a telephone call, but the phone was disconnected. Wildbore, in his desperation, flicked a switch of unknown purpose; it triggered the fire alarm.

Within a minute, five foresters—the entire skeleton staff at Karioi for the holiday period—were out looking for a forest fire. Wildbore and Stuart explained that there was no fire; rather, the Auckland express was in the Whangaehu River. Ranger-in-charge Alan Woodward simply could not believe what he was hearing and asked for it to be repeated. He opened the telephone exchange and contacted Ohakune while John McDonald, fire equipment officer, led the rest to the scene with first aid equipment, stretchers, tools, torches, and a swivel light.

At the river, motorists on the Ohakune side—Somerville, Arthur Dewar Bell, and others—brought survivors from the first carriage, as well as a lucky few plucked from the water who had been in other carriages, up to the road level. They offered what they could in terms of first aid, blankets, and drinks. Somerville recalled that “I carried a little boy up to the top of the bank.” It is impossible to say if this was Ted Brett’s “pillow”, but the location checks out.

Ted found himself blinded by the swivel light and the headlights of cars, and he struggled to keep his eyes open. One rescuer took the “pillow” with urgency and hurried up the steep riverbank, while somebody else offered Ted a drink. He thought it was a bottle of water, only realising it was brandy after taking a big swig.

Calls for help continued to ring out. Ted, remembering them late in life, remarked with characteristic understatement that he did not wish to hear such a thing again. It took over twenty minutes for rescuers to reach Joan and Anne, who had scrambled from their precarious position atop the third carriage onto the bridge girder. In the dark, they dared go no further and risk additional injuries.

A little after midnight, it became clear to those involved in the rescue that they had saved all they could and the search would have to resume in daylight. The last person found alive was a woman buried up to her neck in silt. She had been praying for a quick death when rescuers came upon her. By sheer fluke, she ended up at Raetihi hospital in a bed next to Joan Karam, who discovered this woman was a third survivor from the third carriage.

Survivors were dispersed throughout local hospitals and homes. The Condor (or Conger) family of Karioi accommodated Ted and four other young men. They were caked in silt and oil, and the Forest Service supplied a tanker of water so that there was enough for all five to wash. After Ted bathed, Mrs Condor marvelled at the Pākehā man in front of her, exclaiming “I thought you were Samoan!” It also transpired that one of the other four was a redhead.

On Christmas morning, Ted thumbed a lift to Tangiwai to try to find John and Douglas. The sight of the wreckage was confronting, and the landscape was covered in mud, twisted metal, torn clothes—and, a tragic reminder of the timing, Christmas wrapping paper. Those at the scene told him he should not be there, and that he should go to the Ohakune police station for the list of registered survivors.

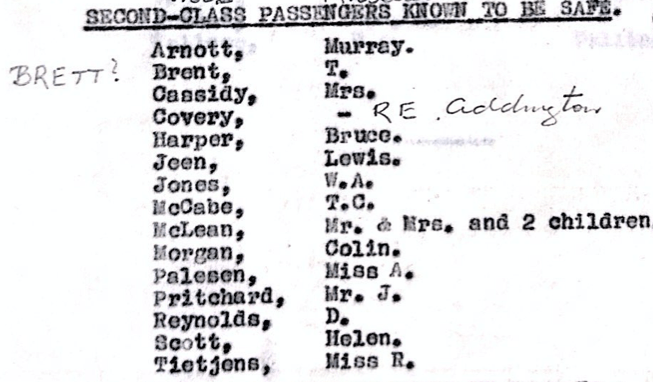

At Ohakune, Ted found John and Douglas’s names were not on the list of survivors—and nor was his, as it had been incorrectly taken down as “T. Brent”. A nearby shopkeeper handed out free ice creams to survivors, while the local butcher and milkman distributed meat, vegetables, and dairy to households hosting them. Ted joined one group for Christmas dinner with the Blinkhorn family. He remembered with gratitude the Blinkhorns’ efforts to make Christmas a little happier, but he could not stop worrying about John and Douglas.

Ted was not the only survivor who returned to the scene seeking answers. A correspondent for the Mail, an Adelaide newspaper, hurriedly wrote an update at the scene. “A boy watching me as I type is still crying. His two pals are dead.” The lad only gave his name as John because “he didn’t want his folk to know he had been crying”. He told the reporter of hearing mothers screaming for their children in the pitch dark. He sobbed again.

Possessions were scattered around the black volcanic soil. A woman’s green overcoat; a baby’s high chair; a small red purse. In a leatherbound diary, the Mail’s correspondent found an entry for 24 December legible: “Left Wellington for Auckland by express to see Queen.”

With no newspapers on Christmas Day, most people learned the news by radio—and, internationally, the Queen herself broke the news to many. She recorded her worldwide Christmas radio broadcast in Auckland, and at the end she addressed her New Zealand subjects directly.

“Last night a most grievous railway accident took place at Tangiwai which will have brought tragedy into many homes and sorrow into all upon this Christmas day. I know there is no one in New Zealand, and indeed throughout the Commonwealth, who will not join with my husband and me in sending to those who mourn a message of sympathy in their loss. I pray that they and all who have been injured may be comforted and strengthened.”

News came in dribs and drabs. Rescuers searched down the river in the summer heat, finding bodies and possessions all the way to the Whangaehu’s mouth on the Tasman Sea. Joan Karam learnt on Boxing Day that the body of her sister Madeline had been found. Three days later, at the morgue in Wellington Hospital, master baker Harold Cockburn identified the body of his 12-year-old son Douglas. The tickets from John Cockburn’s shirt pocket were found under the locomotive—but his body never was.

The night had been clear and the weather fine, but 151 people died in the “Weeping Waters”, the English translation of “Tangiwai”: 148 second class passengers, one first-class passenger, and both locomotive crew. 20 victims were never found and presumed washed out to sea.

21 bodies who could not be identified were buried in a mass grave at Karori Cemetery, Wellington, on 31 December 1953. The Duke of Edinburgh left the royal tour in Hamilton and flew to Wellington to present a wreath during the ceremony on behalf of himself and the Queen. 13 of these bodies were later identified and five reburied elsewhere, so the grave now contains 16 victims. Eight are named. The other eight, in the words of their plaques, are “known unto God”.

To recover from the ordeal, John Holman and his wife took a camping holiday at Ngakuta Bay in the Marlborough Sounds during January. Beyond the reach of the telephone network, they had no idea there was big news waiting. When they returned to Picton on 29 January, Holman bought a paper and read it over their evening meal.

“By God, dear,” he exclaimed to his wife, “I have won the George Medal.”

He was one of four rescuers whom the Queen acknowledged with royal honours. Cyril Ellis and John Holman received the George Medal for their bravery, and William Inglis and Arthur Dewar Bell received the British Empire Medal for the assistance they rendered.

A board of inquiry submitted its report on 23 April 1954, finding that railway staff exhibited “no failure to exercise reasonable care”. It attributed to the disaster to “unpredictable forces of the lahar … of such nature and magnitude as to cause failure of a soundly constructed and maintained bridge”. It made only modest acknowledgement of the heroism of Parker and Redman, who could have jumped clear but “lost their lives in the performance of their duties”.

In 1957, a national memorial was erected at the head of the mass grave in Karori Cemetery. NZR, however, was not enthusiastic about a memorial at the disaster site, and it was not until the 1980s that locals, led by the Ohakune Lions Club, succeeded in establishing one—aided by the momentum of the 35th anniversary, when a National Radio journalist was disappointed to find only a worn wooden cross at the site, the text on it illegible. A granite monument depicting the number plate of the ill-fated locomotive was dedicated on 18 June 1989.

The memorial site has since been expanded considerably during the 2010s, bringing belated closure for many family members. This includes dedicated memorials to Parker, Redman, and Chris Akapita, a worker who died during construction of a replacement bridge, as well as a lookout over the railway bridge and more comprehensive information panels. It is now the most extensive memorial to any New Zealand railway disaster—indeed, it is one of the most substantial in the nation—and a flower station beside the main monument is the nation’s only memorial to survivors of any railway accident.

For the bereaved, the months and years immediately after Tangiwai were hard both emotionally and financially. As the disaster was an “act of God”, NZR was not liable to pay compensation, but its prominence in New Zealand society as one of the largest departments of state meant it made over 150 payments ex gratia to survivors and relatives.

John McAlpine, the Minister of Railways, believed the payments were “reasonably generous … in accordance with what the public would regard as right and proper”. But negotiating compensation was a lengthy process, and many payments were not received until two or more years afterwards. Some families who lost breadwinners depended on the kindness of friends and family to make ends meet. Seven widows with dependent children shared the proceeds of a rugby fundraiser in England played to honour the victims.

New Zealand culture prioritised “getting on with it”: returning to everyday life quickly and not discussing bereavement or mourning publicly. Many of those involved never spoke about what they saw, their experiences mysterious even to close relatives. Men in particular were expected to deal with their emotions without assistance.

Ted was the only survivor among passengers who travelled from Masterton. His joyful reunion with his parents was tempered by his inability to explain to the Cockburns why John and Douglas were not with him, and he did not know what to say to relatives of the other victims either. But one person understood his grief: John and Douglas’s 22-year-old sister Patricia.

“I kept on seeing Pat as she helped me through the rough patches, there were plenty of them,” Ted recalled in 2007, “and this led to my admiration and falling in love with Patricia”. They wed at St Matthew’s Church, Masterton, on 16 April 1955. A year later, Pat gave birth to their first son, Douglas John Brett—my father. Ted died in 2008 aged 72, survived by Pat, three children, and three grandchildren.

Memory is a funny thing. Ted gave two interviews to relatives and wrote his own jottings about the disaster, and almost every aspect that can be cross-checked with other sources matches up. He did, though, consistently misremember one detail: in all three accounts, he describes inclement weather: “it was pouring with rain and it appeared to be set in”, obscuring any view of Ruapehu.

Perhaps escaping from a lahar left a sense that the entire world was wet—because, as the fourth page of the report of the board of inquiry says, “The night was clear and the weather fine.” It was a warm summer evening, one nobody could have expected would leave a scar on the national conscience.

SOURCES

I wrote this narrative principally from newspaper reports, the board of inquiry’s report, and personal testimonies either in my personal collection or found within NZR files at Archives New Zealand—indeed, it was finding some of these last month that motivated me to write this piece. In places I also draw on an academic journal article I have written about the legacies of Tangiwai, which is currently under review and I will add a link when it is (hopefully!) accepted for publication.

The sources used most heavily above are:

- Archives New Zealand, AAAA 158/1/166/18 (witnessed written statement of William Inglis, 2 January 1954)

- Archives New Zealand, ADQD 300/1607/35 (a vast file that contains transcript of Trevor Wildbore’s account via telephone, 25 December 1953, and Robert Somerville’s signed written statement, 26 December 1953)

- Archives New Zealand, ADQD 300/1607/S.2 (another vast file, containing Joan Karam’s account, written 1954)

- Press (Christchurch), 26 December 1953, 8 (Cyril Ellis’s first account to the media) and 30 January 1954, 8 (report of royal honours)

- Mail (Adelaide), 26 December 1953, 1–2 (eyewitness journalist)

- Bruce Mason, “Some Impressions of Events on Christmas Eve, 1953”, Treeline no.36, January 1984 (NZ Forest Service newsletter’s 30th anniversary article written from interviews with the foresters who participated in the rescue)

- Tangiwai Railway Disaster: Report of Board of Inquiry (Wellington: Government Printer, 1954)

- Ted Brett, “Ted’s Jottings”, c.2007, and transcripts of two interviews—one c.1991 with Annie Collins and one from 20 January 2008 with André Brett (me)—all held in my personal collection

There are some conflicting details and many gaps to fill. Arthur Dewar Bell was, as noted above, one of the four men to receive official honours for bravery but none of my sources mention him and searches on Papers Past and Trove bring up little more than reports of him being awarded the British Empire Medal. The Press, 30 January 1954, 8, states that Bell’s wife raised the alarm at the forestry camp in Karioi, but the testimonies of Somerville and Wildbore, and the account in Treeline, all concur that it was those two men who did so.

Interestingly, Somerville and Wildbore both claim the car in which they travelled together was their own. I have not ascertained whose it actually was. I am also unsure of the spelling of the last name of the man they met from another vehicle—in the transcript of Wildbore, he is “Alan Stewart”, while the signed statement from Somerville says “Alan Stuart”. I chose the latter spelling as Wildbore’s account is from a telephone call and the person who transcribed it misspelt other last names, e.g. “Wilddore” and “Summerville”. Relatedly, Ted consistently recalled staying with the “Condor” family of Karioi but an NZR document in ADQD 300/1607/35 refers to him and other survivors staying at “Conger’s store at Karioi”. I went with Grandpa’s version for this piece, as the NZR document has some errors—it is the one screenshotted above with “T. Brent” corrected by hand.

Anyone with any connection to the disaster is more than welcome to email me at andre.brett@curtin.edu.au, especially if you would like to share information for potential use in future tributes. I anticipate writing about this disaster for years to come, and I believe all of us with connections to Tangiwai will be enriched through sharing memories and understanding what happened on that most horrendous Christmas Eve.